The Ḥikmah Center is an intellectual community built upon the three pillars of reading, dialectic, and philosophy. Each pillar has a definition particular to the Ḥikmah Center and contributes to the Center’s overarching vision to educate and produce thoughtful and compassionate individuals who read widely, think deeply, listen earnestly, and speak articulately.

The Ḥikmah Center

Reading

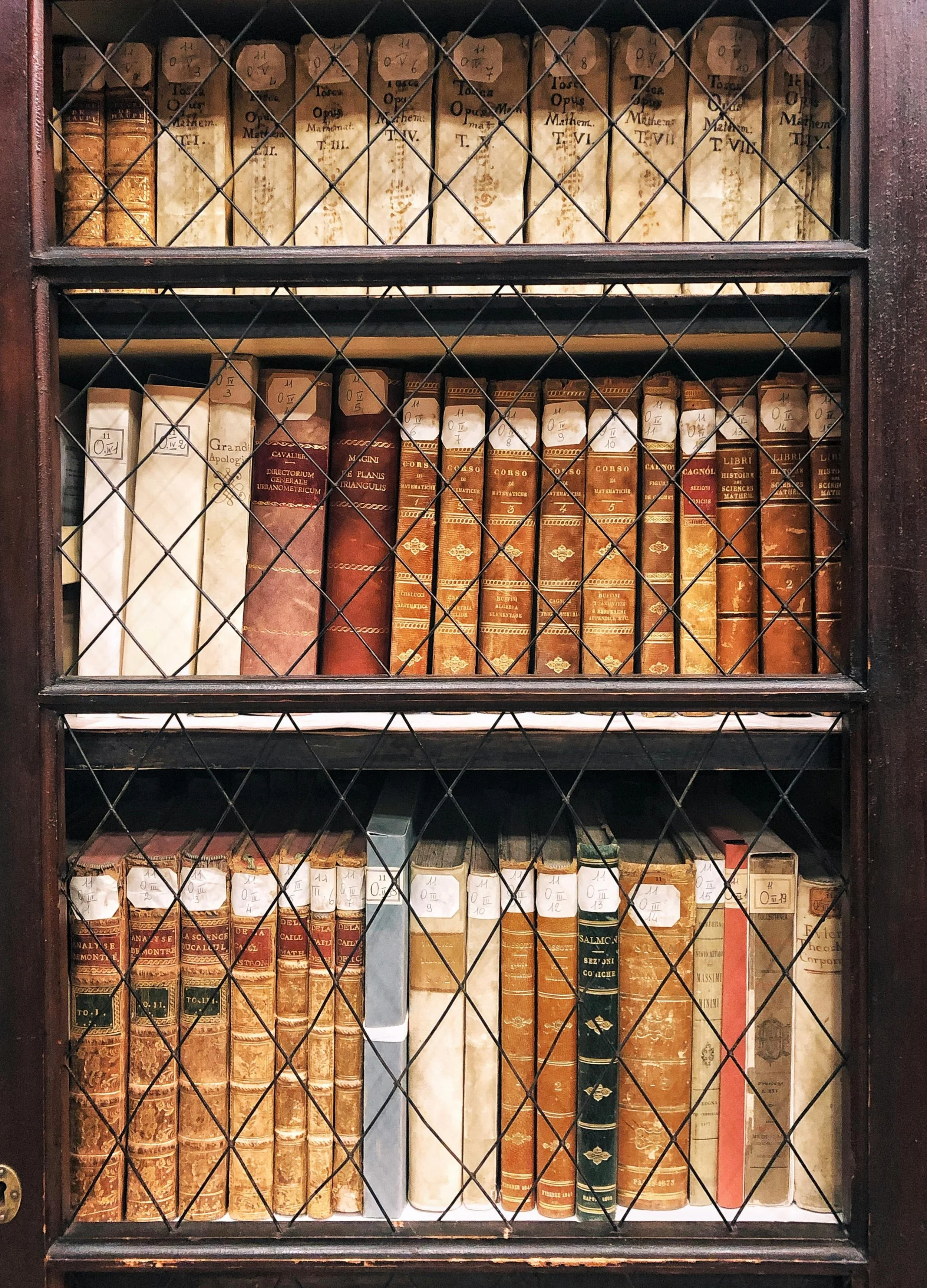

The first pillar of the Ḥikmah Center, reading, is the easiest to understand. Reading is our window into the minds of those luminaries who have sought to capture their ideas in words from the beginning of recorded history. The Ḥikmah Center is specifically interested in reading the great books, the books that are worth reading twice (or thrice or more) and that have charted the course of subsequent thought and writing. To be committed to reading these books means to believe that they remain respectable and relevant to our lives. Beyond reading, however, the Ḥikmah Center seeks to bring people back into the presence of the ideas of these books through conversation and dialectic.

Dialectic

Dialectic refers to the conversational component of the Ḥikmah Center, and it is best understood in relation to its opposites. The first opposite of dialectic is rhetoric. While rhetoric involves a unidirectional display of the speaker’s oratory talents, dialectic involves a constant back-and-forth between discussants who try to ensure that they have understood one another. The second opposite of dialectic is eristic. While eristic stakes out a position on the issue and battles its opponent at all costs, dialectic prompts us to link arms and cooperatively seek the truth. The last opposite of dialectic is didacticism. The didact talks, tells, and teaches; the dialectician asks, listens, and inquires. The student of the didact can sit back and listen like a spectator at a sports game, but the student of the dialectician must think and communicate like one of the players.

Not every opposite is unwelcome at the Ḥikmah Center. Eristic is to be avoided, but rhetoric and didacticism have a limited place. Didacticism, teaching, is particularly important in conveying information to students, but it is always directed toward the eventual engagement of the student through dialectic.

Philosophy

Philosophy, in the context of the Ḥikmah Center, is nothing other than the love of wisdom. It does not refer to any particular doctrine nor to the tendency to destructively critique ideas until everything is doubtful and relative. Rather, philosophy is a disposition that yearns to search, to discover, and to know, especially when it comes to big questions about life, humanity, and the world. Philosophy is the twinkle in the eye of every curious and bright-eyed child who loves to ask “why” and whose spark of wonder has yet to be extinguished by his society. Despite being an innate and, in some ways, childlike curiosity, philosophy also requires a mature commitment to living the consequences of what one believes. The one who knows, and who loves knowing, must also love acting according to what he knows. Otherwise, he is not a true lover of wisdom. In sum, philosophy is both the childlike curiosity that prompts us to begin the journey of reading and dialectic, and the mature completion of our intellects when we actualize our knowledge of Reality.

Culture & Pedagogy

-

In many ways, the Ḥikmah Center is an experiment in purposeful cultural craftsmanship. Each sphere of life has its own culture—the home, the school, the workplace, the coffeeshop. The Ḥikmah Center likewise has a unique culture. Discussants at the Ḥikmah center greet each other with, “What have you been reading recently?” rather than “Did you watch the game last night?” They speak about ideas rather than people or current events. And they seek to understand each other’s interior lives through reflection and compassion.

The Ḥikmah Center uses the title “brother” for all participants, including the instructor. This is because dialectic requires all ideas to be subject to the same level of examination. Ideas receive no special treatment because they happen to be the instructor’s. In order to represent this equality, titles like ustādh, shaykh, and muftī are not used, and all simply refer to each other as “brother.” This also serves to highlight the view that intellectual and moral excellence are not handed down from teacher to student but developed through the hard work of the student.

-

Attending courses at the Ḥikmah Center is more like attending a martial arts class than a movie. The movie-goer reclines and relaxes as the stimulus of the cinema washes over his senses. When courses are like movies, they become performances that students passively enjoy. In contrast, no student of martial arts expects to learn simply by watching the instructor perform the maneuvers. After a demonstration, students must get up, move, grapple, and eventually compete. The Ḥikmah Center’s pedagogy invariably focuses on student participation. Students spend as much time (preferably more time) speaking, conversing, and answering questions as they do listening to the instructor.

The martial arts analogy also applies to the Ḥikmah Center’s view on credentials and certification. The skill of a martial artist comes not from his belt but from his long years of training, for which the belt is only an approximate sign. In addition, no martial artist believes that he has completed his training, that he can relax, and that he will never lose his skill through lack of practice. Martial arts require consistent training. Likewise, the Ḥikmah Center offers no final certification; there is no “end” to the intellectual journey. Ḥikmah Center discussants continue to come and converse, sharpen their dialectical and philosophical fluency, and enjoy the company of the Ḥikmah Center’s intellectual community.

Lastly, the pedagogy of the Ḥikmah Center also resembles that of martial arts insofar as the martial artist’s worth is determined by his own skill. A pedigree of masters back to the founder of the art proves nothing if someone is a punching bag in the ring. Similarly, the Ḥikmah Center does not assign importance to scholastic pedigrees or religious chains of transmission in the absence of intellectual expertise and moral excellence as shown through dialectic and philosophical living.

The martial arts analogy does not apply, very importantly, when it comes to the spirit of competition. Only one fighter comes out of the ring a winner. Dialectic, on the other hand, is not about proving oneself better than anyone else. And philosophy, the third pillar, demands humility and eschews arrogance. The Ḥikmah Center is an inherently cooperative intellectual community.

-

In order to avoid untethered institutional growth, protect the small and intimate spirit of the Ḥikmah Center, and preserve the quality of education, the Ḥikmah Center observes the following limitations.

Class sizes are limited to no more than 20 students.

The Ḥikmah Center is to have no fundraising dinners, widespread advertising, or social media presence.

The Ḥikmah Center is to provide no certification, diploma, or other qualification which may threaten students’ sincere intention to better themselves or which may, by its public recognition, undermine the instructor’s duty to educate his students.

The Ḥikmah Center is to bestow no titles, such as ustādh, shaykh, or muftī, which serve to communicate one’s learning to others but which may become ends in themselves and undermine dialectic by creating authority.